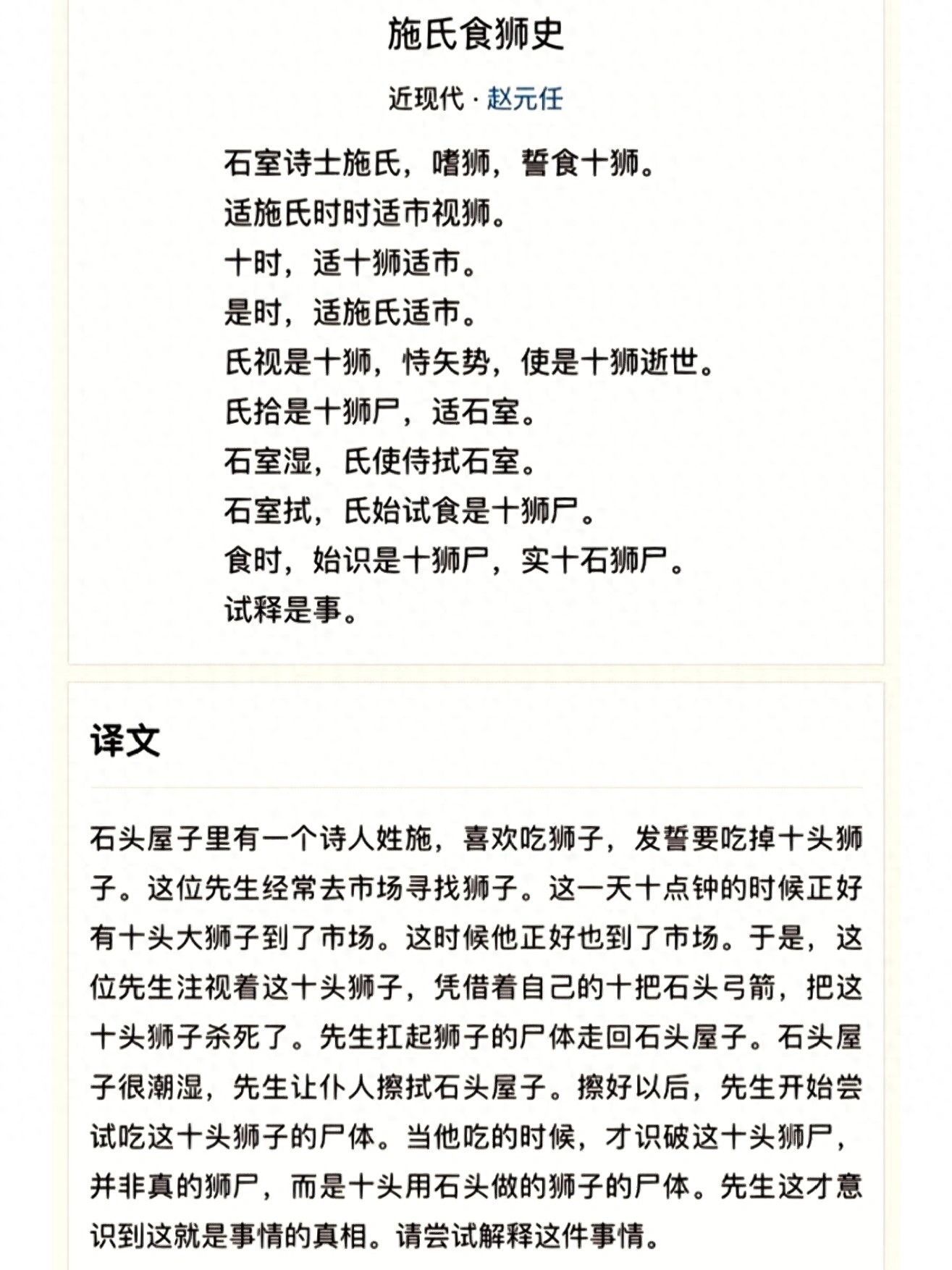

If you’ve ever dipped a toe into the world of learning Mandarin, you’ve probably heard the claim: “Chinese has no grammar.” On Chinese internet forums, this idea is surprisingly common. Native speakers, proud of their linguistic heritage, often point to the lack of verb conjugations, no pesky articles, and a seemingly flexible word order as proof. Someone even went so far as to use the example of “我吃饭了, 我吃了饭, 饭我吃了, 我饭吃了” to argue that they all mean the same thing—therefore, no grammar needed!

But as any serious learner will tell you, this is where the beautiful and brutal reality of the Chinese language begins.

So, what’s really going on? The core of the misunderstanding lies in a Eurocentric view of grammar. As one commenter, lazier_garlic, pointed out, a century ago, Western linguists often equated grammar with inflectional endings. Languages like Latin or Hungarian, with their complex case systems, were seen as having "a lot" of grammar, while Chinese, which is an isolating language, was labeled as having very little. This outdated and, as lazier_garlic calls it, "idiotic" viewpoint has trickled down into popular myth.

The truth is, Chinese doesn't lack grammar; it just trades one set of rules for another.

The Beauty of Particles and Word Order

Instead of conjugating a verb for tense, Chinese uses a sophisticated system of particles and context. Think of 了 (le) for completed actions, 会 (huì) for future intent, or 过 (guo) for past experience. As Wailaowai beautifully puts it, this is "one of the many beauties of Chinese" – no "tedious faffing around with inflections." But don’t be fooled into thinking it's simpler. kristinofcourse clarifies this perfectly: "Right so instead of conjugating a verb you have to add a bunch of words around that verb to add the correct context and provide clear meaning. It's not better or worse, it's just different."

And what about that famous flexible word order? It's not a free-for-all. As LataCogitandi masterfully demonstrated with the "我吃饭了" example, each variation carries a slightly different nuance.

我吃饭了: "I've eaten [so I'm full, thanks]."

饭我吃了: "As for the meal, I ate it." (Implying someone else might not have).

This precise dance of word order is grammar in its purest form. RadioLiar adds that Chinese actually has a "very rigid word order" which replaces the need for the complex declension systems found in languages like German.

Why Do Native Speakers Believe This?

There's a fascinating meta-discussion here about how we learn our own languages. Absolut_Unit hit the nail on the head: "Also most native speakers suck at teaching their language... This applies equally the other way around." Most Chinese speakers acquire the language through intuition and 语感 (yǔgǎn - a feel for the language), not through memorizing grammatical rules. As cringecaptainq noted, this is the Chinese equivalent of an English native speaker struggling to explain the present perfect tense.

This is why, as digbybare wryly advises, "you should never take the word of native speakers as gospels." They are experts in using the language, but not necessarily in dissecting it.

A Welcome Challenge

For learners from the West, the initial relief of "no conjugations!" is quickly replaced by the sobering reality of tones, measure words, and the subtle, critical placement of particles. Cake icon speaks for many of us when they say, "there’s quite a bit of 语法 (yǔfǎ - grammar) that kicks my ass."

Is Chinese grammar "easier"? It depends on what you're comparing it to. Last_Swordfish9135 finds it much simpler than Japanese or Korean. But as lameparadox suggests, if you want true complexity, look to polysynthetic languages like Mohawk, where an entire sentence can be a single word.

In the end, the myth that "Chinese has no grammar" is just that—a myth. It’s a language with a profoundly different grammatical logic, one built on a robust framework of word order, context, and function words. Dismissing it as "primitive" or without rules only prevents a deeper appreciation of its elegance and complexity. So, the next time someone tells you Chinese has no grammar, you can confidently tell them they're missing the whole point. The grammar is there; it’s just playing a different game.